Practice to perfection

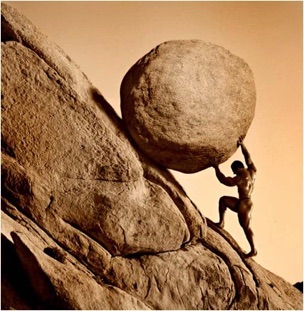

What is the difference between effective practice and practice that is treading water? If we focus on practice as a means to an end, a discipline focused on attainment, our shakuhachi lives will probably be self-limiting. What drives effective practice is the daily rediscovery of a passion to pick the beautiful flute up and blow through it. It’s a great advantage that shakuhachi are beautiful things to have in the hand. Once we have picked it up with delight and curiosity, then we have half a chance at doing something useful with it.

Practice that includes the two important elements of focus and mindfulness has a chance of becoming perfect practice. Perfect practice can arise when you bring enough to the table, for a sufficiently focused time period, that you break through your own perceived boundaries, even if just for an instant. You get a glimpse of your potential, just over the horizon. This is tremendously stimulating and encourages you to pick up the flute the next day, and so on. Sustained, focused practice each day, builds concrete and lasting skills.

The practice time itself, its qualities, its rhythms, its failures, its breakthroughs is the relationship you have with your flute.

Practical Practice

When you work with a teacher, you receive, either directly or indirectly their wisdom and knowledge of a piece, which you internalize and use as your model for your own playing practice.

The path of shakuhachi is really dialoguing with the internal understanding of the piece being played: the dialogue between what you understand and what the flute relationship actually yields in the moment of playing.

It is important to give yourself the full experience of your internal wisdom of a piece. Separate your practice sessions into Workbench and Performance times. On the Workbench, you practice long tones, refine embouchure, practice difficult phrases, strategize breathing points etc.

However, the Performance section is where you honor your internalized understanding of a piece by playing it all the way through, whatever happens: no redos of flubbed notes, no stopping for any reason whatsoever, even if no sound arises at all, even if your pitch is all over the map.

In this manner, you experience the whole composition and get to know it as a whole piece of musical theatre, not as a series of disconnected study phrases, and you can listen, non-judgementally to what actually arises in your sound-making.

You may not be able to render it as fully as you want to, but you can, just the same, experience the complete gestalt of the composition as the beautiful masterpiece that it is.

Over time, and as a consequence of many of these complete experiences of a piece, and your Workbench studies, you begin to own the music.